In 1962, my older brother Paul, then just 4 years old, got gravely ill and was rushed to the hospital.

In 1962, my older brother Paul, then just 4 years old, got gravely ill and was rushed to the hospital.

He would not come home until a year later. His life would be an odyssey of living with diabetes, kidney failure and dialysis, a urostomy most of his life, and all that comes with those conditions. He wasn’t the type of guy who let such things stop him; he graduated from Cornell University and had a successful career in the hotel industry before his untimely passing in 2005 at age 47. While this is not about him, the experience of living with someone with such challenges, and the stories I heard about the hellish year on my family when he was hospitalized always stayed with me.

In 2015 I was asked to attend a hearing at the Town Hall of New Castle, NY to hear local residents speak on the expansion of a local children’s hospital, the Sunshine Home. I expected formalities. The expansion of a children’s hospital didn’t strike me as something anyone would oppose.

In 2015 I was asked to attend a hearing at the Town Hall of New Castle, NY to hear local residents speak on the expansion of a local children’s hospital, the Sunshine Home. I expected formalities. The expansion of a children’s hospital didn’t strike me as something anyone would oppose.

I was incorrect. While the location of the facility was a 34 acre property in a wooded, sparsely populated area of town, a small number of nearby homeowners were vocally opposed to the project. I will not devote more words than the opposition deserve. It was one of the uglier displays of NIMBY (not in my back yard) I’ve ever seen. I supported the project and spoke publicly at the hearings to dismiss the absurd argument put forth that property values would “plummet.” The other arguments against struck me as contrived and implausible.

I will digress just a moment and observe that I was right about values. In the 6 months prior to that 2015 hearing, homes within a mile of the Sunshine Home had a median sale price of $417,500. Today the median price in the last 6 months in that same footprint is $954,000. That’s right, the median sale price more than doubled. Not only that, sales volume was slightly higher this year.

This past week I was contacted by the Sunshine administration and invited to take a tour of the nearly completed expansion. I was able to walk through with the director and got a tour of the magnificent job they did. In addition to increasing the bed count from about 50 to over 120, the resources available to the patients and their families are so extensive and first class that even my big mouth can hardly do it justice. The physical plant itself doesn’t feel like a hospital. It is a bright, airy, colorful lodge.

This past week I was contacted by the Sunshine administration and invited to take a tour of the nearly completed expansion. I was able to walk through with the director and got a tour of the magnificent job they did. In addition to increasing the bed count from about 50 to over 120, the resources available to the patients and their families are so extensive and first class that even my big mouth can hardly do it justice. The physical plant itself doesn’t feel like a hospital. It is a bright, airy, colorful lodge.

It weas surreal to see the improvements. The room for haircuts is a full service spa. The rehabilitation facilities are state of the art. Many medical resources that otherwise would have required transport to outside facilities are now available on premises. The patients even still go to school, in house. Outdoor space is filled with recreational structures, water works, and places for families to sit together and spend time. The sensory gyms are amazing, with interactive electronic touch displays. There is aquatic therapy. The walls and visuals are anything but drab and institutional- it feels more designed by  Willy Wonka than the expected utilitarian feel of a hospital. The utility is still there- it’s the presentation, however, that makes such a huge difference.

Willy Wonka than the expected utilitarian feel of a hospital. The utility is still there- it’s the presentation, however, that makes such a huge difference.

Their website has more visuals than I can post to do it justice, and when you do see what they have done, you should feel some gratitude that you are only an observer. Parents with a child here are in some of the most difficult times of their lives, and the entire setup is geared toward easing their burden as much as possible. I felt emotional walking through the halls and having the upgrades and additions explained.

And throughout the tour, I was exposed to dozens of professionals doing the work of the angels with these children, some as young as preemies. Everyone was smiling and on their game, engaged with making a difference to the child patient in their care. I could imagine what it would have meant to my parents to be able to have my brother in this setting, and what support the parents of the current patients must feel.

I am gratified that I was able to make my small contribution to making this a reality.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link

Buyers don’t need a buyer agent simply because they can open a lockbox and facilitate an offer. To do their job properly, buyer agents have an obligation to perform due diligence on the property they represent their buyers on, and sadly I’m not seeing that all too often. Buyers should expect that their agent will do verify a significant amount of information on behalf of their client:

Buyers don’t need a buyer agent simply because they can open a lockbox and facilitate an offer. To do their job properly, buyer agents have an obligation to perform due diligence on the property they represent their buyers on, and sadly I’m not seeing that all too often. Buyers should expect that their agent will do verify a significant amount of information on behalf of their client:

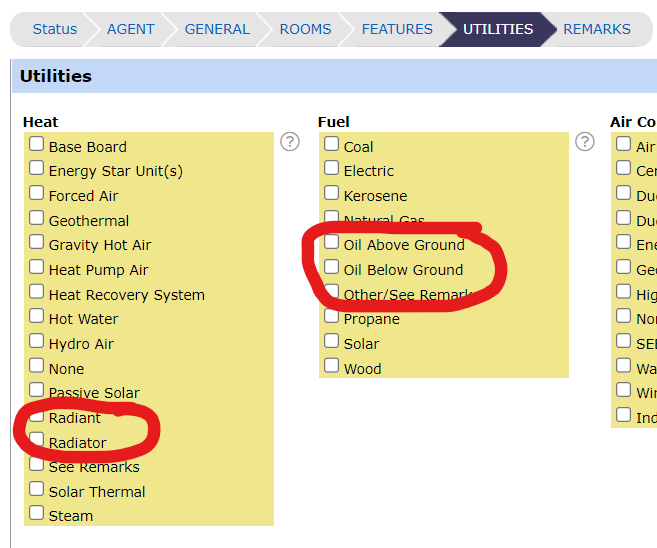

This was clearly being sold by someone who was into do it yourself projects on the property. There was ductwork for central air that was not utilized. There were split units on many walls, part of an extensive system that was hard to piece together for us. A separate flue had been added to the heating system that was unused. There were drainage grates on one side of the house with electrical wires going down into the drain itself. The basement workshop appeared to be an active one, with pipes, hoses, and registers and systems that appeared to be connected to the split units. Outside, electric cables were run alongside the house, partially enclosed with downspouts.

This was clearly being sold by someone who was into do it yourself projects on the property. There was ductwork for central air that was not utilized. There were split units on many walls, part of an extensive system that was hard to piece together for us. A separate flue had been added to the heating system that was unused. There were drainage grates on one side of the house with electrical wires going down into the drain itself. The basement workshop appeared to be an active one, with pipes, hoses, and registers and systems that appeared to be connected to the split units. Outside, electric cables were run alongside the house, partially enclosed with downspouts.

The following is a list of good reasons for a buyer to waive their home inspection:

The following is a list of good reasons for a buyer to waive their home inspection:

Years ago, I was the listing agent on a property where an offer came in significantly below asking price. The pre approval accompanying the offer was for the exact amount offered, tens of thousands of dollars below asking. My client asked why, if they were only approved for $450,000, that they’d even look at a home listed for $500,000.

Years ago, I was the listing agent on a property where an offer came in significantly below asking price. The pre approval accompanying the offer was for the exact amount offered, tens of thousands of dollars below asking. My client asked why, if they were only approved for $450,000, that they’d even look at a home listed for $500,000.

Recently, a client shared with me that a friend advised them to avoid homes on septic and to only buy a home with a public sewer connection.

Recently, a client shared with me that a friend advised them to avoid homes on septic and to only buy a home with a public sewer connection.

This past Sunday I covered for one of our agents and met up with some first time homebuyers for their very first home tour. We had a big day scheduled: 5 confirmed appointments, all of the homes looked good, and the clients were excited to get their dream home.

This past Sunday I covered for one of our agents and met up with some first time homebuyers for their very first home tour. We had a big day scheduled: 5 confirmed appointments, all of the homes looked good, and the clients were excited to get their dream home.

My last two posts have addressed the fact that despite the higher interest rates, it remains a seller’s market because of low inventory of listings. I wrote about why inventory is so low yesterday, and today I’m going to pretend I’m the HUD secretary and Housing Emperor (a position I made up but I’d love that job) to talk about how to get out of the corner the housing market has painted itself into.

My last two posts have addressed the fact that despite the higher interest rates, it remains a seller’s market because of low inventory of listings. I wrote about why inventory is so low yesterday, and today I’m going to pretend I’m the HUD secretary and Housing Emperor (a position I made up but I’d love that job) to talk about how to get out of the corner the housing market has painted itself into.

Yesterday I wrote about the low inventory and the challenges buyers face with supply not measuring up to demand. I did not address the reason why buyers have so little to choose from, and that’s what I’ll attempt to tackle.

Yesterday I wrote about the low inventory and the challenges buyers face with supply not measuring up to demand. I did not address the reason why buyers have so little to choose from, and that’s what I’ll attempt to tackle.

But we aren’t in a typical market here in Westchester and the surrounding areas, and we haven’t been since the Covid pandemic. Right now, the low inventory has resulted in a significant amount of pent up demand, and homes listed around the holidays are enjoying attention that makes it feel like spring despite the temperature. There are legions of prospective home buyers who didn’t have much luck in the spring or summer who are still looking in earnest.

But we aren’t in a typical market here in Westchester and the surrounding areas, and we haven’t been since the Covid pandemic. Right now, the low inventory has resulted in a significant amount of pent up demand, and homes listed around the holidays are enjoying attention that makes it feel like spring despite the temperature. There are legions of prospective home buyers who didn’t have much luck in the spring or summer who are still looking in earnest.

$449,000 will buy you a condominium with Hudson Views like the one I just closed on. The MLS description for the property are as follows:

$449,000 will buy you a condominium with Hudson Views like the one I just closed on. The MLS description for the property are as follows:

First, some background: In late 2019, Long Island Newsday published the shocking results of an investigation where reporters of different ethnicities and races went undercover as prospective homebuyers and the different ways they were treated by the real estate agents they engaged.

First, some background: In late 2019, Long Island Newsday published the shocking results of an investigation where reporters of different ethnicities and races went undercover as prospective homebuyers and the different ways they were treated by the real estate agents they engaged.

I don’t think I’ve seen the following thought written anywhere lately, but I’ll say it:

I don’t think I’ve seen the following thought written anywhere lately, but I’ll say it:

I got a question from a client about the effect that installing solar panels might have on their home’s value. It’s a good question, actually. Years ago when hurricanes knocked out power in our area for more than a week, I opined that backup generators would become the new status symbol. While I wasn’t wrong, green initiatives are gaining momentum and NAR even has a Green Housing certification for agents.

I got a question from a client about the effect that installing solar panels might have on their home’s value. It’s a good question, actually. Years ago when hurricanes knocked out power in our area for more than a week, I opined that backup generators would become the new status symbol. While I wasn’t wrong, green initiatives are gaining momentum and NAR even has a Green Housing certification for agents.

For Agents: Open House Parking Etiquette

One agent, unfortunately, only parked less than halfway in with their clients behind, and just one car fit behind them. I asked them to move up, and they demurred, promising to just be a “moment.” The “moment” was 20 minutes. I asked a second time, and was told they didn’t want to be blocked in. Well, yeah, waiting a few minutes for others to have their turn is better than blocking them out and not even giving them a chance to enter.

Some people parked down the street a bit where some temporary street parking was plausible. But one couple left, and that sucks.

We are all in this together. Selfish or tone deaf behavior when you are quite frankly a guest at someone’s home isn’t a good look, and it isn’t very collegial either. A minor inconvenience is part of the equation when the alternative is to alienate others. There are multiple offers on the house. It will sell. The seller will be happy. But I can’t get that couple out of my head who were so friendly who waited nearly 20 minutes, then decided to leave. I spoke with them. They should have bene able to enter. That’s not fair to them, and the results notwithstanding, my seller client would want them to have a chance also.